Hair Cells and Hearing Loss: Dr. Aaron Steiner’s Remarkable Research

October 27, 2018

While many of us think of humans and fish as two very distinct species, the two share a large portion of genetic material, according to Dr. Aaron Steiner, an associate professor of Biology at Pace. In fact, Steiner is using this to link the two in a rather unique way; his research, which is supported by a three-year $378,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health, seeks to understand how scientists could regrow the sensory cells that humans hear with.

In the human ear, hair cells are used to sense movement to send signals to our brains, which is how we hear. However, since humans cannot regenerate these cells, hearing will be lost if these cells die or are damaged. With zebrafish, which are being used as a model, these hair cells do regrow, and Steiner’s research hopes to find if any shared genes may be responsible for this regeneration.

“What I’m trying to figure out is whether some gene or genes have been either activated or inactivated in the human ear that prevent [hair cells] from regrowing,” said Steiner. “If we can play with that, if we can stop the function of a gene or over activate a gene, we might be able to restore the regeneration of hair cells in the human ear and restore hearing.”

While Steiner’s current work has a unique focus, his research combines both his background and his interests. Steiner has experience in developmental biology, and he used to study how embryos develop at a very early stage. However, he was also interested in the field of communication, and knew that he wanted to study something within that area.

During his postdoctoral studies, Steiner founded a lab at Rockefeller University that allowed him to study both. At this lab, he tried to identify genes that could regulate the regeneration of hair cells, and he found hundreds of genes that are differentially regulated during regeneration. His work at Pace, then, is a continuation of this research that further narrows this to just a few genes.

“The preliminary evidence is there, but we don’t have solid evidence yet,” Steiner said. “But, some of these genes may affect the rate of regeneration of sensory hair cells. If that’s the case, the next step would be to identify whether these genes are also expressed in the human ear, and whether we can tweak their activity in the human ear.”

As Steiner explained, there has, evolutionarily, been some change from our predecessors that caused hair cells to stop regenerating. The goal of his research, then, tries to figure out what those changes may have been and to reverse them.

“This is what biology really is,” he added. “When you think of what biology is, you think of what’s in the textbook, and you think of memorizing a bunch of facts and a bunch of terms, but biology is alive, and there are so many active areas of research.”

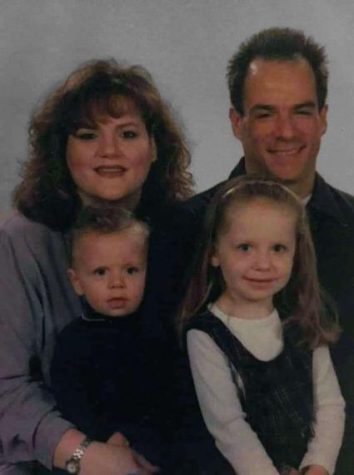

In addition to this research, which Steiner joked about as being most of his life, the professor has a love for birdwatching and photography, and he has been busy being a dad to his 1-year-old daughter.

“I also used to go to a lot of concerts, which I realized later on in life may be part of why I went into this field,” Steiner began. “So, I may be searching for a cure to my own, self-inflicted deafness from going to too many concerts.”