Pace Changes the Language of Sexual Assault

After months of revision, Pace has updated its sexual assault policy and redefined consent on campus.

According to a school-wide e-mail from NYC Dean for Students, Marijo Russell-O’Grady and Interim Dean for Students on Pleasantville, Rachel Carpenter, these updates also include a new sexual assault resources website and a guide to options, resources, and support.

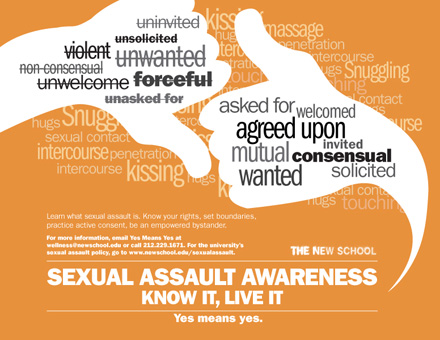

Consent is now defined affirmatively (“yes means yes”), matching the definition for State University of New York (SUNY) schools.

Pace’s policy offers that consent is “a conscious, voluntary, mutually understandable, equal, respectful, continuous, and freely communicated agreement to participate in a sexual encounter.”

It further clarifies that neither “lack of protest or resistance” nor silence can be interpreted as consent, that it cannot be assumed based on “previous consensual encounters” or a relationship, and that it must be ongoing and is revocable.

Despite this, the introduction of affirmative consent on college campuses has raised some questions nationally. Some anticipate that the expectation for ongoing consent is too high, providing unreasonable responsibility for those involved.

According to a CNN.com article, the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) is among the leading adversaries of affirmative consent for this reason.

“It is impracticable for the government to require students to obtain affirmative consent at each stage of a physical encounter, especially if students must later prove they successfully did so in a campus hearing,” John Cohn, legislative and policy director of FIRE, told CNN. “In reality, requiring students to obtain affirmative consent will render a great deal of legal sexual activity ‘sexual assault.’”

For criminal justice professor and Westchester County attorney Maryellen Martirano, the impracticality comes not within the ongoingness of consent, but whether or not it is verbally expressed.

“To actually say ‘[yes],’ I think it’s unrealistic, but there are a lot of things one could say that would indicate it,” said Martirano, who is specialized in domestic violence and sexual assault cases and formerly served on the Westchester County Domestic Violence Council. “Silence is difficult, but if someone is being absolutely silent and expressing body language that is clearly [affirmative], then I think that’s okay.”

Consent, according to the updated Pace policy, can also not be given if an individual is “incapacitated.”

This term is also defined within the Sex-Based Misconduct Policy and Procedure.

“Incapacitation is a state where someone cannot make rational, reasoned decisions. A person may be incapacitated due to mental disability, sleep, unconsciousness, physical restraint, or from the consumption (voluntary or otherwise) of incapacitating drugs or quantities of alcohol.”

The policy offers that incapacitation should be deducted based upon “physical cues” including “slurred speech, bloodshot eyes, the odor of alcohol on a person’s breath, inability to maintain balance, vomiting, unusual or irrational behavior, and unconsciousness.”

For Martirano, the consideration of behavior and body language rather than the number of drinks one imbibed is crucial.

“There are different levels of intoxication, and that’s really what we’re talking about,” Martirano said. “If someone can’t stand up, would you think that they can give consent? No. If I have a couple of drinks, and I’m sitting and talking and fine, yes, I can give consent.”

An amnesty policy for individuals reporting incidents was also introduced to Pace at the beginning of the current school year. Residence Directors and Assistants were responsible for describing this policy to all residents upon move-in.

According to the SUNY protocols, amnesty policies are aimed at encouraging students to report incidents. The policy “will grant immunity for drug, alcohol, and other…violations for students reporting.”

“The whole idea is never to be afraid to tell someone if somebody needs help…this keeps that from happening,” Assistant Dean for Community Standards and Compliance Debbie Levesque said. “Most important is that you get help, and then we worry about the rest of it later.”

Further, Pace’s “Guide to Options, Resources, and Support” defines confidential and non-confidential resources for reporting an assault.

According to the guide, confidential resources consist of Health Services, the Counseling Center, and Campus Chaplain Sister Susan Becker.

An additional resource for Pace students is the Women’s Justice Center, which operates out of Pace Law School in White Plains and provides legal counseling and services for victims of sexual assault.

“Sometimes people don’t know what to do. A confidential resource helps a person realize what all of their options are, and then lets them step as they’re ready to go through,” Levesque said.

She added that ideally, confidential resources would help an individual to preserve evidence and provide them with the strength to eventually report.

Non-confidential resources, otherwise identified as mandated reporters, are legally obligated to report any information regarding sexual assault.

Mandated reporters include security personnel, Deans for Students, Residence Hall Directors and Assistants, Human Resources staff and University administrators, according to Pace’s sexual assault policies.

Last year’s federal Not Alone Report suggested the explicit presentation and distinction of such resources.

The Not Alone Report was the first report to be established by the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault, a group formed and signed off on by President Barack Obama in January 2014.

“When you talk to someone that you think is a confidential resource, you need to be sure of that,” Levesque said. “I think the federal government felt that [this] needed to be strongly worded, so that when someone is reporting an assault, [they] have control over what happens and where information goes.”

In addition to helping universities to develop and conduct individualized “climate surveys,” the Not Alone Report seeks to clarify existing campus requirements prescribed by both Title IX and the Clery Act.

In accordance with the Clery and Campus Crime Statistics Acts, Pace publishes campus security statistics annually at the beginning of October.

In its 2014 report, which includes information for 2011–2013, the school counted one sexual offense in 2013. However, its U.S. Department of Education report and website report conflict as to whether this offense was forcible or non-forcible.

Both the 2011 and 2012 reports state no sexual offenses.

Based upon a collection of university security statistics, the Boston Globe reported that campus sexual assault incidents had risen dramatically between 2012 and 2013.

“A survey of information from more than two dozen of the largest New England colleges found that reports of ‘forcible sex offenses’ climbed by 40 percent overall between 2012 and 2013, according to a Globe review of data that colleges provided in annual federally mandated reports released last week.”

Additionally, an NJ.com article noted that the number of sexual assaults on New Jersey college campuses had more than doubled in the past five years, according to Clery Act reports and “amid growing scrutiny into sexual violence on campuses nationwide.”

Some attribute these growing numbers to an increased comfort by students to report based upon changing policies.

Levesque held this belief.

“If you have no reports, does that mean that there are really no reports, or that people don’t trust you?” she asked.

This increase in reports, paired with a 2014 survey disclosing that 40 percent of participating universities had not conducted a sexual assault investigation in four years, contributes to nationwide pressure on college campuses to improve their policies.

“We’re looking to make sure students know well in advance who they can go to in order to process something without fear that information is going to be given to somebody when they’re not prepared for that to happen,” Levesque said. “People really need to know what their options are and that they can retain control from the beginning to the end.”

During the summer of 2014, all Residential Life staff members received updated sexual assault training in accordance with the Not Alone Report.

“It was important for us to talk to RAs because sometimes people will want to tell [them] something and say ‘but you can’t tell anybody,’” Levesque said. “It was important for us to be able to give them enough training that they would be able to say, ‘but I can’t do that. If you need to talk to me about something, before you say something, understand that I need to report it to someone else.’”

Additional plans include training student leaders in the Step-Up Program, a national bystander intervention program that presented at Pace in September.

Incoming students will also complete a series of sexual assault education programs beginning with an online summer webinar and continuing through summer orientation and their University 101 classes.

“In years past, we were a little more reluctant to talk about human sexuality, reproduction, birth control, but now I think there’s a recognition that [we need to] do our best to help students who find themselves in those situations,” Levesque said.

University officials hope that a better understanding of this policy will prevent incidents, such as that which occurred on Pace’s New York campus last year, from taking place.

According to a Huffington Post article, “Pace University forced the victim of an alleged sexual assault into an investigation, found the alleged rapist not responsible without saying why, and then attempted to require both students to attend a program on alcohol and date rape, a complaint filed with the Education Department claims.”

An emphasis on reporter control within the new policy was expressed specifically by Levesque, who saw the case as an opportunity to educate and improve.

“What’s most important is that the person who is reporting this is really the person that’s directing the outcome,” she said. “I think sometimes people don’t report because they think once [they] do that, no matter what [they] say, it’s going to take on a life of its own, and I think the clarification in the policy is going to make sure that a person knows that they don’t ever lose control.”

Levesque is additionally responsible for the creation of PAR[2]C (Pace Advisors for Respectful Relating and Consent), which is comprised of both faculty and students and meets bi-weekly to discuss campus policies and programming.

For more information, resources, and help, visit pace.edu/sexual-assault.

Your donation supports independent, student-run journalism at Pace University. Support the Pace Chronicle to help cover publishing costs.