Michael Ferraro: His Sister’s Keeper

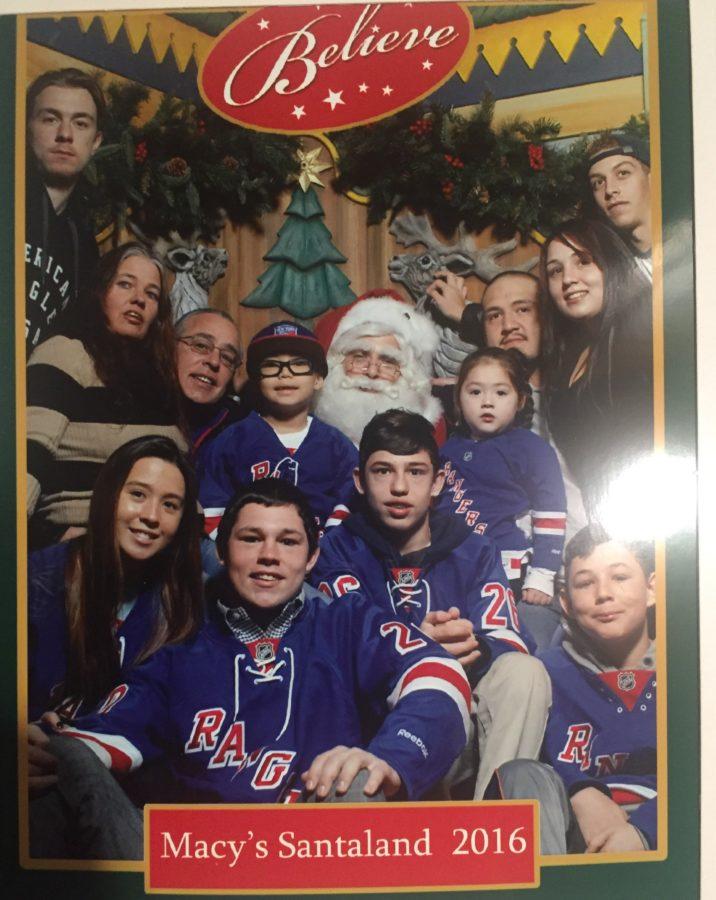

The inception of “My Brother’s Keeper” was very much inspired by sophomore Michael Ferraro’s (front row, second left) own experience with his sister Aimee Ferraro’s (back row, second right) drug addiction. Photo Courtesy of Michael Ferraro.

It was 9 a.m. on a spring weekend in 2005 when Pace sophomore Michael Ferraro was awakened by his older sister, Aimee Ferraro, asking for a favor. She asked him if he could urinate in a pill bottle for her to use to fake a drug test.

Utterly shocked and confused, he agreed and did what his sister asked of him because she was his sister and needed his help. Her parents, however, didn’t fall for the ruse and confronted her later that evening. It was then that Michael Ferraro realized his sister was a drug addict.

“It was just one of those days that throughout the day you kind of keep questioning, ‘did I do what was right or did I do what was wrong?’ because you don’t know what you’re doing,” said Ferraro, who was eight-years-old at the time. “I go, ‘Listen, that’s my sister, that’s my blood, I’m going to help her.’ My parents ended up talking to me about it saying you can’t do this and I end up finding out at a young age what it all was.”

His family moved to Long Island from Queens earlier that year and they were under the assumption the area was good.

It was on Long Island, though, where Aimee Ferraro began experimenting with marijuana, and other drugs, progressively getting worse, before ultimately becoming addicted to heroin. She had several ill-fated attempts at rehabilitation before her parents kicked her out of the house when she was 16.

“I think I hated my sister and not in the sense I actually hated her, but I was so hurt by everything that was going on that I just kept my distance,” said Ferraro, who’s one of four children. “You kind of put this person on a pedestal and you look up to them no matter what and something so drastic happens and you totally look at this person a different way. I didn’t know how to look at her any other way.

“When I got older [Aimee] would call me and try to make a relationship, but I’d still push her away. It came to a point where I had to realize that you can’t really give her another chance because I kept giving her chances and it would just go out the drain, but let her [help herself] and just let it go.”

Michael Ferraro did get farther from her not just emotionally, but physically. He attended the Peddie School—a college preparatory and boarding school in Hightstown, NJ—on a football scholarship.

It was there that he met Dan Riscoe. Ferraro, a 5-foot-11-inches safety, formed a bond with his new teammate and friend when he learned that Riscoe’s brother was also a drug addict.

Ferraro always wanted to do something to help people affected by drugs, but could never figure out what his “next step” should be. Meeting Riscoe turned out to be that step. The two sophomores began sharing stories and it led to the birth of “My Brother’s Keeper,” an organization that helped others deal with similar situations.

“The whole idea wasn’t to be something we all cried about, and it was ok to cry, but it was to learn, to understand, and this is something people hold close to them,” said Ferraro, a business management major. “The idea was, let’s make a safe place that is trustworthy to help each other understand, learn, and kind of feel better about a situation.”

My Brother’s Keeper started out small with fewer than a dozen people coming to meetings. As time went on and word got out around Peddie, people’s curiosity piqued. There were more than 50 students attending events and meetings by Ferraro’s senior year.

It became an official club at Peddie and is still operational, but Ferraro’s mission now is to make it go nationally.

That day when Ferraro was eight, however, is what sparked his desire to help, not only his sister but anyone whose friends or family members are addicted to drugs.

Aimee Ferraro, 26-years-old now, is four years sober, married with two children, and declined an interview because she’s “moved on” from that day and that part of her life.

“I think I did the right thing [that day]; I think if I would have said no [to Aimee], I wouldn’t be where I am today,” Ferraro said. “If I would have said no, maybe my sister would have went to someone else, maybe the situation would have changed, and maybe my parents might have never caught her. So, I’m still glad I said yes because in a way it helped me grow up faster, learn, and mature.”

Your donation supports independent, student-run journalism at Pace University. Support the Pace Chronicle to help cover publishing costs.