Education, Not Incarceration, At the Heart of OPB’s Week of Illumination

March 5, 2015

When Prof. Kimberly Collica-Cox began her work at Taconic Correctional Facility’s HIV prison-based peer program, there was little research on the effects of such educational programs on women. Now, people are increasingly convinced that education is key to improving this country’s correctional system.

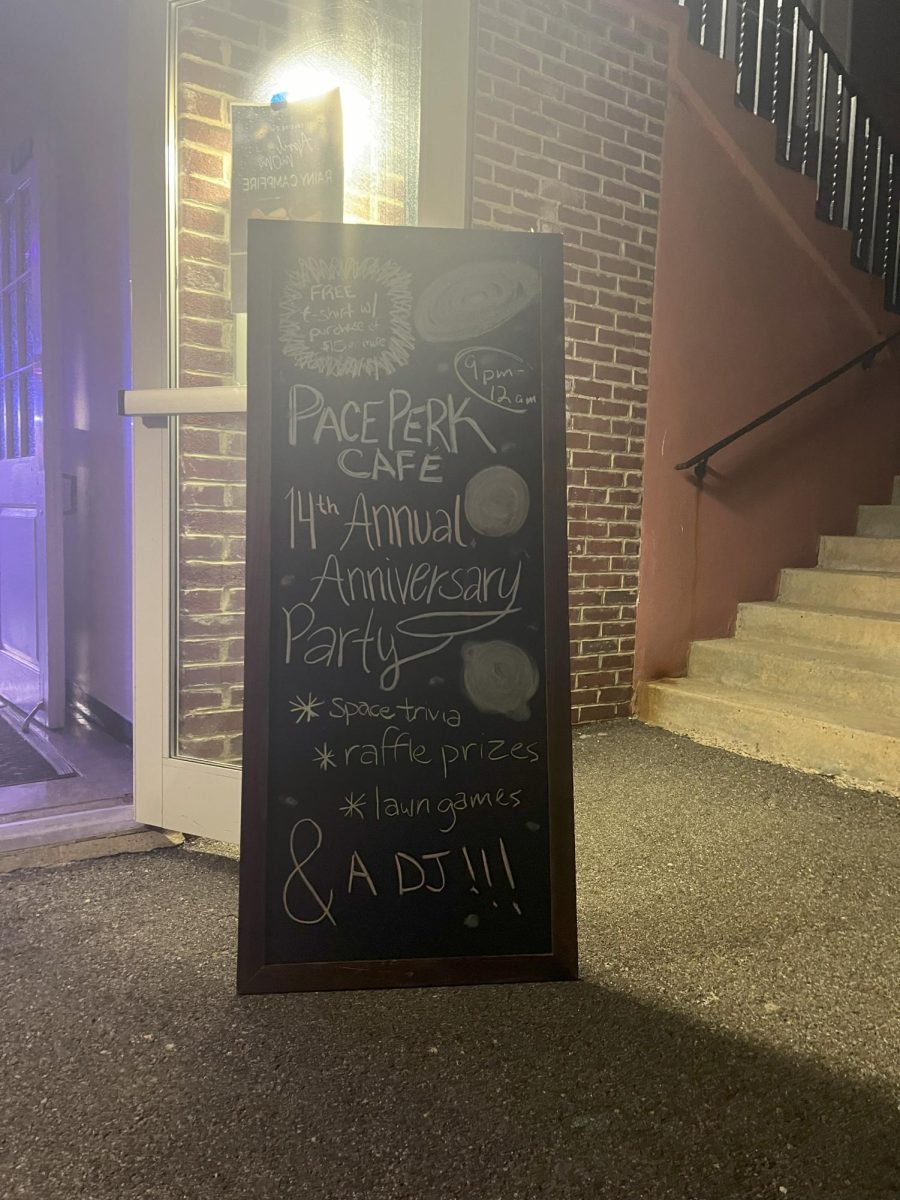

This idea was at the center of Omega Phi Beta (OPB) Sorority’s “Illiterate and Incarcerated” event, held in Butcher Suite on Feb. 25.

The event was part of OPB’s sixth annual Week of Illumination, with the theme “the Convict Chronicles.” Collica-Cox, who teaches in the Criminal Justice and Security Department, and Rachel Simon, Assistant Director of Multicultural Affairs & Diversity, were guest speakers at the event.

Collica-Cox began asking if there should be educational programs in prison, and whether prison is just about punishment. She then presented data on the current incarcerated population in the U.S.

Forty percent of the two million people in prison have no high school diploma, and 60 percent of inmates are functionally illiterate, which means that, though they have some reading and writing skills, they have difficulty filling out a job application. This last number goes up to 85 percent in juveniles.

Inmates also test usually two to three degrees lower than their last education level.

Simon spoke of her experience at Bedford Hills Maximum Security Prison. She emphasized the educational programs’ efforts to give students a college experience and to treat them with respect.

A central question throughout the event was whether it is a privilege for incarcerated women to get an education.

Another concern was where the resources for prison education programs should come from, since some people show hesitation at the idea of tax dollars being used for this purpose, especially with the high costs of college. But according to Collica-Cox, if current federal grants directed to prison education were distributed among the total number of college students, each student would receive less than $5.

The recidivism rate—the likelihood of an offender returning to prison—is less than 10 percent when prisoners take part of college education programs, in contrast with the overall 67 percent recidivism rate of all inmates.

According to senior and OPB sister Ariana Abramson, who ran the event, when the difference in these two recidivism rates is looked at next to the Unites States’ current spending—approximately 39 billion tax dollars allocated to its prison system—the solution seems clear.

“It costs less to educate than to incarcerate,” Abramson said, pointing out that if more inmates received an education, the recidivism rate would diminish, along with the cost of keeping people in prison.

As Collica-Cox’s studies progressed, she noticed that disciplinary infractions went down substantially for many of the women who began working in educational programs. Additionally, she noted, self-esteem and confidence levels increased.

“When the women were finally eligible for release, they were able to obtain paid positions in the field of HIV,” she said.

“Education, not incarceration, can help to not only cut spending on the prison system, but also to give these women the tools to rebuild their lives,” Abramson said.

Abramson also said the problem begins outside prisons, as people go through the education system. Minorities are especially vulnerable to dropping out of school, she said, which increases their chances of depending on welfare or going to prison.

For senior Sania Azhar, education is a universal right.

“An education is basic to conduct yourself in the world. How do we expect inmates to improve if they don’t receive it?” Azhar said. “Prison should be punishment enough. Prisoners have a right to go on with their lives, let the correctional really help correct them.”

“Most of these women who left, never returned to prison, which made me consider the fact that these programs were not just about education, they were about redirection,” Collica-Cox said.

Students who want to get involved can volunteer their time with non-for-profit agencies such as the Fortune Society, Women’s Prison Association, and the Osborne Association.

“Students can also consider joining the criminal justice society—open to all majors—or they can major/minor in criminal justice studies,” said Collica-Cox, whose present research focuses on female inmates, rehabilitation, reintegration, and HIV, in addition to the career trajectories of female executives in corrections.